One Battle After Another

Unpacking Nigeria’s Conflicts Without Turning Pain into Competition

Written by Emmanuel Ehi Echoga | Seeking Veritas Columnist | | Sankarsingh-Gonsalves Productions

Why Suffering Isn’t a Scorecard

There’s a dangerous reflex that often appears whenever violence and poverty collide in the headlines: the instinct to compare grief. Every time I see conversations about war, insurgency or famine devolve into tallying tragedies: “we’ve lost more lives than you” or “our suffering is worse” I’m reminded of how that language erases the people at the centre of the crisis. Pain doesn’t need to win a contest to be valid. It doesn’t matter whether the bomb that destroyed your home was dropped in Gaza or Borno; the shrapnel still wounds, the displacement still uproots families, the grief still fractures futures.

I want to trace how these conflicts emerged, what they cost, and why the “one battle after another” metaphor isn’t just a catchy title but a lived reality.

I write as an Idoma man from Benue State who has watched his home region cycle through conflicts. Coming from a family of several Officers in the Nigerian Military, my Elder brother serves as a pilot in the Nigerian Air Force and has flown missions over some of the most contested parts of the north‑east. Through his stories and my own research, I’ve come to see that what happens in Maiduguri isn’t simply a “Nigerian issue”, it is intertwined with global economics, climate change, colonial borders, and the stories we tell about who belongs where. In this piece, I want to trace how these conflicts emerged, what they cost, and why the “one battle after another” metaphor isn’t just a catchy title but a lived reality.

The Reality of Nigerian Conflicts

Boko Haram’s insurgency began as a fringe sect preaching against Western education. It escalated into an all‑out rebellion that has battered north‑eastern states for over a decade. According to policy analysts, the insurgency has killed tens of thousands of people and displaced millions. Those numbers conceal families huddled in camps, children growing up without schools, and farmers who can no longer plant. When my brother talks about flying over villages where roofs used to be, he doesn’t describe “killing extremists”; he talks about escorting aid convoys, praying their trucks aren’t ambushed, and feeling helpless when he hears that the camp he protected last week was attacked the next.

The drivers of Boko Haram are not merely “religious fanaticism” or “anti‑Western sentiment.” Decades of state neglect, corruption, and inequality created fertile ground for recruitment. Many young men who joined were unemployed, angry and disillusioned. Climate change has compounded the crisis: shrinking Lake Chad forced pastoralists and farmers to compete for dwindling water and grazing land. With few opportunities, insurgent wages and a sense of belonging became seductive.

Herdsmen-Farmer Violence in the Middle Belt

The conflict in the north isn’t the only crisis amongst others in varying context across regions and urban/rural areas. In the Middle Belt, including my home state of Benue, clashes between Fulani herdsmen and farming communities have intensified. These fights are often painted as ethnic or religious, but at their core are disputes over land and survival. Desertification in the north pushes nomadic herds southward. Farmers, who have tilled ancestral fields for generations, see grazing cattle as an invasion. Traditional conflict‑resolution structures, elders’ councils and community agreements, have been eroded by politics, arms proliferation and impunity.

When herdsmen attack a village, the headlines rarely record the historical droughts, the broken irrigation schemes or the politicians who incite anger to win votes. When farmers retaliate, no one talks about the years of stolen harvests. The result is a cycle of vengeance that looks like a religious or ethnic war on the surface but is fundamentally about resources and the state’s failure to manage them.

Systemic Issues Driving Violence

Behind both conflicts are systemic drivers: poverty, poor education, youth unemployment, corruption and a lack of social safety nets. Nigeria’s population is young and rapidly growing. Without jobs, education or hope, millions of youths are left vulnerable to recruitment by criminal or extremist groups. Corruption siphons funds meant for roads, schools and health clinics. A lack of accountability means perpetrators often escape justice, encouraging further violence. All of these factors feed into the sense of abandonment that makes insurgent propaganda resonate.

It’s important to emphasise that while Nigeria’s conflicts share threads with global crises: climate change, migration, geopolitical interference, they also require local, context‑driven solutions. Comparing Boko Haram to ISIS or the farmer–herdsman clashes to Israeli‑Palestinian tensions can obscure local nuance and agency. Our goal is not to equate tragedies but to understand the specific conditions that enable them.

Outside Perspectives & Global Engagement

From Canada to the United States and Europe, Nigeria often appears in newsfeeds when there is a mass kidnapping or a gruesome attack. Asides records sent in entertainment industries and other special cases, this selective visibility leads many outsiders to assume that the entire country is engulfed in chaos. It also creates a paternalistic lens through which Western audiences see Nigerians as passive victims waiting to be rescued.

Nigeria’s conflicts do have global implications: they destabilise West Africa, fuel refugee flows, and provide safe havens for transnational extremists. Western governments and NGOs respond with humanitarian aid, counter‑terrorism training and occasional airstrikes. These interventions can help: my brother’s squadron has trained with foreign pilots, and humanitarian convoys often rely on international funding. Yet there is a risk when outsiders dictate solutions without understanding community dynamics.

Personal Insight-A Pilot’s View from the Cockpit

Beneath the uniforms are people wrestling with trauma, guilt, and resilience in equal measure.

I spoke with a junior officer in the Nigerian Air Force, who continues a family legacy of service passed down from a late senior naval officer. For security and privacy reasons, his name and rank are withheld. He has transported injured and fallen soldiers, seen bullet holes too often, attended too many burials, and doesn’t speak like a spokesperson.

On Complex Causes: How have you experienced the Boko Haram and Herdsmen conflicts on the ground? What do people often misunderstand about them?

“Having operated in affected regions, I’ve seen that these conflicts are not as one-dimensional as they’re often portrayed. Boko Haram isn’t just a “religious extremist” problem, it’s a product of decades of neglect, poverty, and disillusionment. The herdsmen-farmer clashes, too, are often oversimplified as ethnic or religious, when in reality they’re rooted in land pressure, climate change, and the collapse of traditional conflict-resolution systems. On the ground, it’s a tragic mix of survival instincts and systemic failure. What most people miss is how much ordinary civilians, and even combatants, are trapped by circumstances far beyond their control.”

On Human Toll on Officers and Families: How do Military Actions affect Officers and their families?

“Military life in conflict zones tests everything: patience, mental health, family bonds. There’s a silent toll that rarely makes the headlines. Officers spend long stretches in austere conditions, juggling duty and the emotional strain of distance from loved ones. Families live with uncertainty and fear, often with little institutional support. Public discussions tend to focus on battlefield outcomes, victories or losses, but not the human fatigue behind them. Beneath the uniforms are people wrestling with trauma, guilt, and resilience in equal measure.”

His words remind me that behind every statistic is a person carrying a weight we rarely acknowledge.

One Battle After Another – A Cultural Metaphor

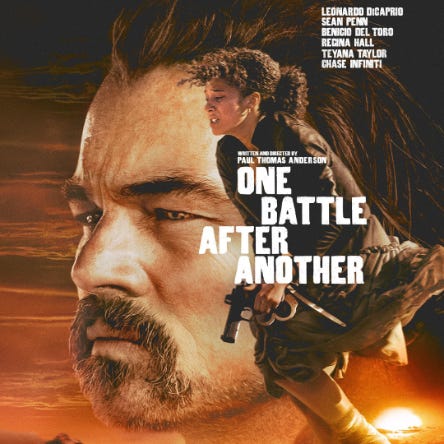

Paul Thomas Anderson’s film One Battle After Another (featuring Leonardo Di Caprio, Teyana Taylor and Benicio Del Toro) doesn’t tell a Nigerian story, but its structure resonates. The film interweaves lives caught in cycles of violence, trauma and fleeting moments of joy. It explores how grief can harden into vengeance, how love persists amidst war, and how people trapped by systemic forces still find ways to resist or reinvent themselves.

In our context, the title becomes a metaphor: Nigeria’s battles are not just military, they are battles over land, resources, narratives, identity, and the right to dignity. Each victory often reveals the next struggle waiting underneath.

Hope & Innovation – Shifting from War to Collaboration

Across Nigeria, grassroots organisations are mediating between herdsmen and farmers, providing trauma counselling to survivors, and equipping youth with vocational skills. Women’s groups in Borno run microfinance schemes for widows. Community radio stations broadcast peace messages in local languages. Young entrepreneurs are building apps to report attacks and organise rapid responses. These initiatives might not make global headlines, but they are the seeds of sustainable peace.

Nollywood, Afrobeats and the nascent gaming sector illustrate that culture is more than art; it is an economic engine and a vehicle for healing. When a Nigerian film about courage after insurgency becomes a hit, it counters Boko Haram’s message of fear. When an indie video game from Lagos invites players to negotiate disputes instead of shooting enemies, it subtly teaches conflict‑resolution.

Peacebuilding doesn’t always look like treaties or press releases.

We are not only documenting conflict, we are reimagining what life can look like after it. From indie animators in Jos, to writers in Kaduna, to gamers in Lagos building their own tournaments from scratch, a creative rebellion is blooming.

Platforms like Africa Comicade are making this tangible. Through initiatives like the Gamathon, they’ve built bridges between digital creatives across Africa, fostering collaboration that transcends borders. Countless independent visionaries like Michael Oscar, Marie Lora-Mungai, Eyram Tawia, and Mo Abudu, and creators on LinkedIn and other platforms are spotlighting African voices not just for visibility, but for ownership. They are building industries rooted in culture, capable of generating jobs, shifting narratives, and dignifying lived experiences.

My own project, Echo Culture, believes that gaming, music and film can bridge cultures and inspire empathy. Investing in these industries means empowering youth to tell their own stories, earn a living and imagine futures beyond war.

This is what excites me. That peacebuilding doesn’t always look like treaties or press releases. Sometimes, it’s a game developed in Ghana that teaches conflict resolution. Or a Nollywood series that reframes what justice can feel like.

Nigeria, and Africa at large, has never lacked stories. What we’ve lacked is ownership, platform, and the freedom to tell them whole. But that is changing. And I, for one, want to be part of that change, not just surviving the battles, but learning to write what comes after.

About the Author: Emmanuel Ehi Echoga is a Nigerian writer, storyteller, and podcast host. He is the founder of Echo Culture, a creative hub exploring how storytelling in gaming, music, and film can shift perspectives and bridge cultures. | Echoga is the author of Inbetween Worlds

Sankarsingh-Gonsalves Productions 2026 ©️

References

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) – 2023 Nigeria Report

Highlights climate change, inequality, and youth unemployment as conflict multipliers.

World Bank – Fragility, Conflict, and Violence Report (2024)

Discusses systemic governance issues and displacement in fragile states, including Nigeria.

https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/fragilityconflictviolence

ReliefWeb / OCHA – Nigeria Humanitarian Snapshot (2024)

Consolidated humanitarian statistics on North-East Nigeria (Borno, Adamawa, Yobe).

https://reliefweb.int/country/nga

FAO & IFAD – Climate-Security Nexus in the Sahel (2023)

Examines how drought, desertification, and grazing pressures fuel regional conflict.

https://www.fao.org/emergencies

International Crisis Group – Stopping Nigeria’s Spiralling Farmer-Herder Violence (2021)

Landmark report identifying structural roots and mitigation pathways. https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/west-africa/nigeria/262-stopping-nigerias-spiralling-farmer-herder-violence

BBC Africa Eye / Premium Times investigations (2023–2024)

Field reporting on displacement, insurgency fatigue, and survivor stories in Benue & Borno.

"From Canada to the United States and Europe, Nigeria often appears in newsfeeds when there is a mass kidnapping or a gruesome attack." And as pointed out, this leads to a very skewed and very incomplete impression. I appreciate how this article counters that by offering a broader, more fulsome view for consideration.