Building a Culture of Support for First Responders and Moving Beyond Awareness

By Suzz Sandalwood | The mental health challenges faced by first responders stem from a combination of structural, cultural, leadership, and systemic factors within their organizations.

Written by Suzz Sandalwood | Seeking Veritas Columnist | Sankarsingh-Gonsalves Productions

In my previous post, I highlighted the mental and emotional toll that the job of a first responder can have that is often masked by a culture that prioritizes silence over self-care. As I continue to write about this, I want to explore how we can continue to create a culture where vulnerability is seen not as weakness, but as an essential part of this work.

To start this conversation, I would like to share a real-life storyabout a first responder.

A man named James had a childhood dream of becoming a Police Officer. He began his career in the Canadian Armed Forces and as a Paramedic, which we know has its own risks of trauma exposure. He always felt a calling to do a job that served others. When he got the call to join the police force in 2001, he quickly excelled and moved through the police organization in many units while still working as a paramedic. He was on his way to what looked like a reputable and promising career. He was known as the paramedic officer, a firearms expert and the go to person for anything that was complex and required covert analysis.

THE THINGS YOU CANNOT UNSEE AS A FIRST RESPONDER

After six years on the job, while part of the dive team, there was a call to a lake to search for a missing teen that had fallen overboard on a boat. James and his team searched the lake for a few days. From the stories shared with me, James was relentless in his attempt to find the body. The family watched, waiting by the shore and while he knew this was not going to be a life saving call, he wanted to make sure the family had a body to lay to rest however they wanted to.

James eventually found the teen under water. He carefully lifted him into the boat so the family could not see his lifeless body and then the dive team came to shore. It has been shared with me that James was incredibly compassionate and calm during his death notification, answered any questions the family had and they were very grateful for his empathy and professionalism. He was given praise by his police services for his ability to work through horrific weather conditions and navigating a black lake to find this body for the family.

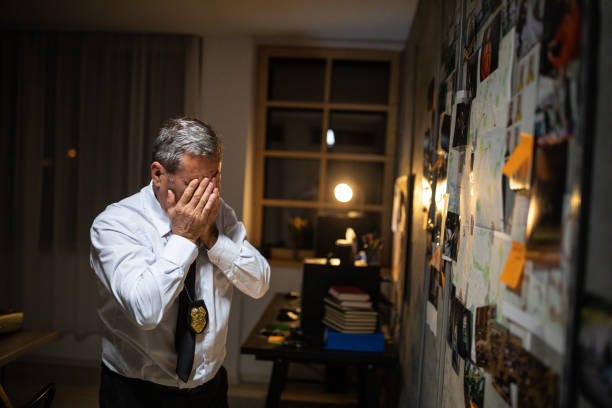

A few months later, James sat with a gun at his kitchen table, drank himself into a blackout and passed out before he could use the gun on himself. He did not take his own life that night but alcohol became his companion. His work performance began to be impacted. He was calling in sick all the time and then one dayhe just didn’t show up for his shift. When a wellness call was initiated to check on him, he admitted for the first time that he was struggling with alcohol and he needed help but no one knew the breaking point for him was from that call at the lake.

The Duty Inspector at the time was incredibly supportive and caring in the moment and the police association supported him in going to addiction treatment. But, this began a very turbulent ride for a first responder who thrived on being resilient, stoic, and hailed a hero. His gun was taken away and he was assigned to desk duty even though he successfully completed addiction treatment. He felt like his work was trying to make an example out of him and he struggled coping with this and relapsed. He interpreted this experience at the time as proof that if you are struggling, your job will be in jeopardy. This was not easy for James to acceptand even though he eventually got sober for good, less visible addictions creeped in while the impact of his trauma exposure lingered silently. He quickly switched on the “I am fine” persona. A persona that is too easy for first responders and called a skill. His struggle was not visible to those that knew him in a professionally capacity but not so silent in his personal life. James had sleeping issues, was always hyper vigilant in public, had to sit facing the doors in any restaurant, became mistrustful of everyone around him, withdrew in his personal life and stopped being social.

THE WEIGHT OF TRAUMA AND SILENCE

James walked into every yearly psych evaluation after that time and told them what they wanted to hear. Over the years he moved through the organization continuing to hold many different titles; Death Investigator, Sex Assault Investigator, Coach Training Officer, Dive Team Member and Constable Detective in CIB and ICE. He was very well known and respected in these positions and other police services, made headlines for dismantling an international child pornography ring and saving the life of a woman whose partner was trying to kill her.

There are stories that still circulate today about him rushing into a bar to take down a murder suspect in a very skilled, tactically safe and professional way. But he also saw more death and trauma than many in the first responder field navigating both policing and paramedic roles. He chose to stay silent because of what happened the one time he asked for help.

I will share at this point that aside from the fact that I have a professional background working with first responders and their families, I was also James’ spouse. I witnessed how much he suffered after he came forward and asked for help. I too was significantly impacted by his addictions and mental health struggles. I was always worried about his mental health and addiction symptoms and experienced a great deal of anxiety because of the ongoing effect this had on our marriage.

James died in 2021 as a result of brain cancer. He was still actively engaged in certain addictions outside of being sober for years from alcohol and was still struggling with his mental health when he died. Society pays attention when a first responder dies by suicide but there are many still living that need our attention now before they die whether by suicide or not.

WE CANNOT IGNORE THE ELEPHANT IN THE ROOM

Since that time, we have seen many movements in attempt to destigmatize and humanize struggle for first responder culture. There have been numerous internal and external resources and supports that exist now that did not exist even ten years ago. We have begun to move beyond simply recognizing the problem and focus on actionable, meaningful support systems but cracks in this system are still there. Mental health programs, peer-driven support, and partnerships with mental health agencies are increasingly recognized as essential tools to help first responders manage trauma. But there’s an elephant in the room we cannot ignore: leadership.

The mental health challenges faced by first responders stem from a combination of structural, cultural, leadership, and systemic factors within their organizations. Understanding these moving parts is crucial for developing effective interventions to support these professionals. It is important to implement internal leadership development programs that focus on mental health literacy, emotional intelligence, and the creation of supportive work environments. By fostering a culture that prioritizes mental well-being and destigmatizes seeking help, first responder organizations can better support their personnel.

Organizational structures can significantly impact the mental well-being of first responders. When you look at factors like inadequate staffing, excessive workloads, and insufficient resources, these all can contribute to elevated stress levels. And when you consider systemic issues, including policies and procedures that don’t adequately prioritize mental health, this can also contribute to the struggles of first responders. I spoke to two officers this week who shared that prioritizing their mental health and taking time off came with guilt at times because if their absence impacted the shift and something went seriously wrong, that would be another burden to carry.

THE NARRATIVE OF MENTAL HEALTH CONVERSATIONS GET LOST IN THE CHAIN OF COMMAND

Some leaders in first responder organizations have earned their positions through rank and have been tasked to lead without resources through the complexities of mental health and trauma. Sometimes, they themselves are carrying unaddressed wounds from years of exposure to tragedy and as a result they may struggle to recognize or effectively know how to support those under their command. This disconnect can inadvertently perpetuate the cycle of silence and suffering, making it clear that we cannot talk about improving first responder mental health without addressing the human dynamics of leadership within these organizations.

We have to acknowledge that many leaders in first responder agencies are products of the same culture they now oversee. They may have been promoted because of their excellent technical skills, dedication, years of service, or rank but not necessarily their ability to support teams grappling with trauma. This comes with great responsibility for leaders who may also feel like they are in a position where they cannot show vulnerability.

Some leaders may not recognize the signs of a first responder in distress because they have never been taught to identify them. Others might feel ill-equipped to have difficult conversations about mental health, fearing they’ll say the wrong thing because there is already so much tension between divisions in police services. And for those leaders who carry their own unhealed wounds, stepping into this role might feel like it is reopening old scars they’ve worked hard to ignore. It can be easy to point fingers and look for blame in why there is silence but I can’t help wonder if a big part of that is because there is not enough leadership training on how to navigate a situation like one of your officers is sitting at the table with a gun drinking themselves into oblivion. Sending them to treatment and calling it support or assigning them to “other duties” does not translate well to empathy and understanding at the human level it needs to be.

Leaders who openly acknowledge their own struggles with mental health, stress, and trauma are critical in normalizing these conversations and I have seen a few that are starting to do this and hope this continues. When senior leaders are transparent about their own emotional experiences, it sends a powerful message to the entire organization that it’s okay to seek help, talk about their challenges, and not be expected to shoulder the burden in isolation. These leaders can help dismantle the toxic stigma that often surrounds mental health within first responder cultures where tough, silent endurance has been prioritized over emotional expression.

LEADERSHIP AS A DOUBLE EDGE SWORD

First responders live at the crossroads of life and death, shouldering responsibilities that few outside their world can even understand. They rush into danger and witness human suffering in its rawest forms. They are trained to suppress their emotional reactions to chaos. They learn to compartmentalize, to stay calm under pressure, and to prioritize others’ needs above their own. These skills are essential in the moment but can become a double-edged sword. When the shift ends, the weight of what they’ve witnessed doesn’t always vanish and it can linger, unspoken and unresolved.

For all the training they receive to handle emergencies, there’s little guidance on how to navigate life after the call and how to go home, decompress, and protect their mental and emotional well-being. And some, like James, will develop alternative coping mechanisms like drinking to numb the pain and to avoid confronting their feelings.

A CALL FOR ACTION FROM THE INSIDE OUT

I want to believe that change is possible. In Ontario, Canada, where I write this from, there are examples of change that are beginning to transform the approach to mental health and leadership. The foundation of this transformation rests on four pillars: mental health programs, healthy workplace teams, peer-driven support and partnerships with mental health agencies. But while these pillars are vital, they are only effective if used and in order to do that, more work needs to be done from the inside out.

Without compassionate and trauma-informed leadership, even the best mental health programs will fall short. Their success is contingent upon the commitment and capability of organizational leadership. Addressing the mental health needs of first responders requires a multifaceted approach that includes not only the availability of resources but also the cultivation of a supportive and informed leadership structure.

Leadership development programs must include training on trauma-informed care, emotional intelligence, and active listening. Leaders need to be given the tools to recognize when their team members are struggling and the courage to respond with empathy and action. At its core, leadership in first responder organizations is about humanity. It’s about seeing the person behind the uniform. A human-heart-centered leader doesn’t dismiss a first responder’s pain or frustration as weakness. They recognize it as a sign that the job is taking its toll, and they step in not with judgment or punishment but with compassion. They lead by example, seeking therapy or peer support for their own struggles and sharing their journey openly to break down the stigma. They understand that while the work is a business, the people doing it are not machines. Their value is not measured solely by their output or ability to push through pain. They are human beings with limits, vulnerabilities, and a deep need for connection and care.

The path forward requires commitment and courage from the leaders who lead their teams. We have to keep pushing back the outdated notion that strength means silence or that leadership is purely about operational success. When leaders choose to lead with humanity, they don’t just save lives in the field, they save the lives of those who serve. This will have a ripple effect, not only in the workplace but in the homes of first responders, where the impact of trauma is felt just as deeply.

Next Week on 911 Community

In next week’s article I will share more on the often-overlooked impact that the first responder lifestyle has on their families and how the demands of the job, uncertainty, and emotional strain of these roles can affect those at home.

About the Author: Suzz Sandalwood is an Advanced Certified Clinical Trauma and Addiction Specialist and a Certified Grief Counsellor. She has extensive professional and lived experience in first responder, addiction, and grief communities. | Connect with the author: https://suzzsandalwood.com/

Sankarsingh-Gonsalves Productions. 2025 ©️

Tags:

#traumarecovery #911community #firstresponders #PoliceCommunity #police #firefighters #ems #trauma #mentalhealth #ptsd #leadership #HumanizingTheBadge #lineofduty #blog #writer #substack #endthestigma

Thank you Suzz for this well written, informed and compassionate article. You touch on so many excellent points but the one that stood out for me was the importance of training leaders to be "transparent about their own emotional experiences." Although I couldn't agree more, I believe it becomes difficult when first responder organizations hire leaders who have not spent substantial time in the field. I believe this is a critical first step in being able to even begin to build genuine compassionate and trauma-informed leaders. Without having experienced first-hand the sacrifice and toll that decades of responding to human suffering in its rawest forms can have on them and their peers, the development of our leaders can only go so far. This is not to say that training cannot develop a more compassionate appreciation for what the job extracts from those they lead, or that others in senior leadership roles with first responder experience can't be assigned this role, but it's been my experience that those who best understand the importance of the message you are trying to convey, are the ones who have had years of experiencing it front and centre. Thank you so much for what you are doing.